Inspirations:

Little wonder that Schiaparelli the fashion designer never ran dry of inspiration: all she had to do was dip into the well spring of images and colours of her childhood memories. The celestial globe in the Lincei Library showing the planets in their zodiacal houses was undoubtedly the inspiration for her Zodiac Collection, considered one of her most brilliant presentations. When she was old enough, her father allowed her to examine illuminated medieval manuscripts filled with fanciful figures hand painted under blue and blood red skies and guided her through his illustrated books of saints. Among her most striking up tilted hats of 1935 were to be found the Saint Halo’s. She would also use mantillas, Fra Angelico hoods and and monastic cowls.

Her use of scarlet and mauve combined with the Peruvian pink of the Incas recalled from her father’s books was to become one of her hallmarks. Black and white is a typical Schiaparelli colour combination as well. It was Puccini’s operas La Bohème , Tosca and Madame Butterfly with their frank approach to contemporary matters appealed most to her in her adolescent years.

During her youth, the new accent on the machine- in photography, motion pictures, gramophone recordings, transport and communication- greatly influenced her.

Married to Compte William de Wendt de Kerlor, they arrived in New York in 1919. Elsa was assailed by the new images, materials and sounds of the 20th century that she was to absorb and then reproduce in French Fashion. Gabrielle Picabia introduced her to the artistic circles in New York and then in Paris : Marcel Duchamps Alfred Stieglitz and his group, including Baron de Meyer, Edward Steichen and Man Ray.

Paul Poiret also played a significant part in the life and career of Elsa. Who was more suitable to be his successor in originality, intelligence and sympathy for the avant garde? Harper’s Bazaar comments in 1934 that she is the feminine Paul Poiret.

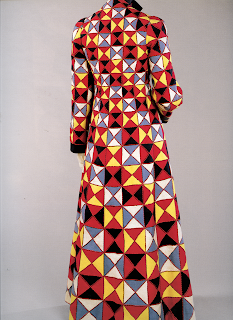

She was also inspired by Sonia Delauney. Sonia had opened a little fashion house, and Elsa was struck by her adaptation of Cubism to clothes, her revolutionary cutting of coats from tapestries, her use of vivid bi coloured hat veils, and especially of her introduction of red and green wigs.

Rarely if ever, has a couturier used people’s gifts to greater effect than did Elsa Schiaparelli. She possessed the humility and was shrewd enough to face her weaknesses that she chose the best collaborators in each field. Many great artists of the period worked with Elsa: Dali, Cocteau, Vertes, van Dongen, Giacometti, Christian Bérard are some of them. In fashion photography: Man Ray, Baron de Meyer, Edward Steichen, Cecil Beaton.

Starting up:

An American friend of Blanche, Mrs. Hartley wanted to invest in a French business. Impressed by the success of Elsa’s sweaters, she persuaded her to produce a small collection mainly of sports clothes. In late 1925 she bought a tiny dress house; Maison Lambal, located not far from Place Vandome on the corner of Rue St Honoré and rue du 29 Juillet. She chooses Mr. Kahn , a successful businessman as a sleeping partner, because he was French, knew about fashion through being associated in the backing of Vionnet, and had large holdings in the Galerie Lafayette department store.

Collections: Diplay No 1

Her sweaters unlike Patou’s and Chanel’s were hand made by an Armenian refugee from the Turkish massacre Aroosiag Mikaelian, Mike. They would soon prove to be so popular that all the great couturiers copied the idea. In several of these she made her first revolutionary use of the emerging materials of the century with “kasha”, a very elastic new woolen fabric just patented by Rodier and introduced by Patou, resistant to wear and tear and designed to make the figure appear slimmer. Then, exploiting the idea of interchangeable separates whose possibilities she has realized as a girl in Rome , she added knitted jackets, and skirts generally of crepe de chine in colours matching the sweaters. The scarf became an integral part of the sweater, an innovation of her own. The simple practicality and use of artistically treated fabrics announced her coming contribution to the new relationship between artists, craftsmen and industry pioneered by Art Deco. Art Deco stressed the practical and functional: the style was classical, symmetrical and rectilinear. Much of it reflected the geometrical forms which had so impressed Elsa in New York City . In her designs she used spots; revived balanced patterns, and combined ultra modern geometrical abstractions and Futuristic treatments with the stark simplicity and angularity taken from Cubism.

Whereas Chanel and later Balenciaga merely experimented with synthetics, Elsa frankly imposed them on haute couture. It is very much linked to the activities of Colcombet family, pioneering artificial fabrics and launched almost all the new ones in France after 1920. In 1930 Schiaparelli presented a sports ensemble and coat in rayon for the first time and endorsed “rayon is like the times we live in – gay colourful luminous, it is so pliable to work with and so luxurious in appearance launders the perfection.” In 1932 she introduced a new and exquisite synthetic “peau d’ange” jersey, called Jersarelli, a deeply crinkled fine ribbed reversible crepe, shiny on one side and matt on the other, and jersala a synthetic silk jersey with a satiny finish. She was the first to employ the initial cellulose acetate, Setilose in 1934.

The practical innovation that caused the greatest stir is her sliding or lightening fastener: the zip. From 1930, she used zip for pockets of beach costumes, in haute couture in 1935 on evening gown even on hats. She had them specially made in plastic and boldly emphasized them by attaching Indian tassels or baroque pearls, having them dyed in a colour contrasting with the fabric. She used zipper for transforming garments such as zipper backs,

up for dinner and down for formal occasions, or the fastened shoulder seem, when zipped up the dress was informal, when unzipped it was appropriate for lunch or tea.

For Display No 2, her new beach ensembles shown in July 1928, right after Vionnet’s collection, New York herald commented that she had brought more original ideas into sportswear than all the other designers put together. In the coming years she refined the beach and resort pyjamas in sailcloth or in jersey for housewear and informal entertaining. She developed an overall pyjama. In 1931 she hit with trouser skirts and divided skirts integrated in to her interchangeables

She launches fur scarves she herself wore in public, one in ermine to go with a black tweet suit which was at that time a revolutionary idea. Accessories were always of the greatest importance to Schiaparelli. From the beginning she had invented myriad ways of making scarves interesting, she hit the American headlines in 1929 with her removable fox or astrakhan collars and slip on and off scarf collars. The Mad Cap in 1930, a tiny little cap like a tube that took whatever shape the wearer desired.

1930 she made her first evening gown. An, evening dress with a short jacket, as a new idea staggered Paris fashion. Elsa noted later, proved to be the one most successful dress of her career. Her hallmarks became glamorous and practical boleros and bolera and jacket suit .Completely unheard 3 years ago, in 1931 she was already recognized as the leading smart Paris designer. In 1934, her four hundred employees were turning out between seven and eight thousand garments a year.

Celebrity endorsement:

Wooing famous actresses was one thing, but in the twenties leader of high society disdained to appear in fashion magazines. The breakthrough for Elsa however, came almost at once. American Vogue featured a sketch of the young Duchess of Sutherland in a black and white Schiaparelli frock in may 1928 , French Vogue in December published a sketch of Comtesse M. de Polignac in a Schiaparelli ensemble, in December 1930 Princess Pignatelli, in 1931 Comptesse de Bourbon Parme was shown in two pages of Schiaparelli sketches. Also Daisy Fellowes, Nancy Cunard and movie stars such as Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo, having the ideal figure for it, generally credited with launching the masculine Schiaparelli style. Joan Crawford and Bette Davis were the embodiment par excellence of the Schiaparelli Lady.

Style:

Recalling the madness of the early twenties where people yearned to dress up again and escape in to the romantic and theatrical, longing to be jolted and swooped up into some fun and games, the moment was ripe for Elsa and she was ripe for it. Instinctively she knew that this was the time to be shocking, and the world became her theme. In the history of fashion, few designers have interpreted the mood of the day more accurately or energetically than did Elsa. Vibrantly in tune with her times, she foresaw needs before they were felt and answered them with a gift for anticipation that was at times uncanny.

The only point of similarity between Chanel and Schiaparelli is that both their extraordinary careers began with this emblem of the twenties, the sweater. However the eight years 1921 -1929 separating Chanel’s first collection and Schiaparelli’s were decisive in Paris fashion, for the two women were more than competitors, they were antagonists.Chanel claimed that dress designing was a profession, Schiaparelli insisted that it was an art. Balenciaga, the designer’s designer, the last great titan of haute couture, was of Elsa’s opinion. Balenciaga always said that Schiaparelli was the only true artist in fashion.

Whereas Chanel stood for calculated ease and luxurious simplicity, Schiaparelli was tough and brash, offering sensational effects, in bright and bold colours. In the battle of sexes, her clothes reflected an entire social revolution: defensive by day, and aggressively seductive by night. Her daytime clothes dubbed hard chick, had a militant, masculine quality. The New York inspired Skyscraper silhouette concealed feminine vulnerability in an almost belligerent manner: straight vertical lines and widened squared shoulders. This style made hips seem narrower, more like a man’s. She reduced the lines of her Skyscraper Silhouette to a quite and satisfying sanity in 1933, rounded the shoulders, introduced the raglan sleeve in 1935. To increase the volume, she emphasized upper arms and made them appear more muscular by padding ordinary sleeves, building up mutton leg sleeves. Already enlarged, she was inflating these in 1933 into gigantic cathedral organ sleeves or fluted sleeves. Masculine uniforms which inspired her included Cossack jacket coats, train guard’s uniforms and red riding coats which she adapted into evening redingotes and later into severe looking hostess gowns. The sumptuous cloaks of Venetian Doges came in the widest variety of silk weaves By 1939 all Paris fashion had taken on the hard military look anticipated by her.

Schiaparelli unleashed in 1934 the four wings of the Stormy weather silhouette called the Typhoon line: forward, backward, upward, downward, bringing everything in motion, hurling it all into the fleet and windswept lines of a speed bat or aero plane in to the swirls of sails caught in gusts, even blowing furs forward so that they strained out and up, anticipating the streamline. The following silhouettes are, in 1939 cigarette and mermaid silhouettes, 1936 Stratospheric and Aeroplane silhouettes including her new parachute dress. 1938 Schiaparelli produced 4 of her most imaginative shows. In February Circus Collection, Pagan (Forest) collection in April, Zodiac Collection in August, Commedia del Arte collection in October being her last great collection.

She also gave each collection a theme. For practical purposes this lent greater overall harmony and encouraged a more precise creativity. It also allowed her to streak off on unprecedented flights of imagination, humour and theatricality. For these collections she designed gowns of special fabrics, appropriately printed our embroidered, with corresponding buttons, jewels, trimmings and accessories.

Changed lifestyle demanded practicality. This was her Cash and Carry collection (1939) featuring jackets with huge pouch pockets to enable a women to take essentials with her, retain the freedom of her hands and yet manage to look feminine. Since the lack of servants was becoming an acute problem in current life, she offered gardening dresses and kitchen clothes so that her customers might mow lawns, prune roses and do their own cooking and still look attractive.

She designed skirts which brought the old country bicycling costumes into town, and insisted on the wrap around skirts as worn over gaily printed bloomers and matching blouses, thus preparing for the new mode of transport to be imposed by wartime restrictions. She launched the transformable dress. Like that the woman of the world, deprived of her Hispano or Bugatti, could emerge from the metro to attend a formal dinner party or to dine at Maxim’s by merely pulling a ribbon to lengthen her short skirted day dress into an ankle length evening gown. The fabric of one white coat supposedly withstood poisonous gas.

Her concept of clothes was architectural: the body was to be used as the frame is used in a building. Instead of following the indulating curves of the flesh, she followed the length of the hard, bony structure. The variations in line and detail always had to keep a close relation to this frame. The more the planes of the body were respected the more the garment had acquired vitality. For her one could add or take away lower or raise modify and accentuate a garment but the harmony had to remain. The Greek understood this rule and gave to their goddesses the serenity of perfect form with the appearance of freedom. Much of this Elsa learned from Paul Poiret. Like him she did not see a dress merely in terms of stitches. Like him she never drew designs for models; but sketched new ideas in order to suggest them to her junior designers and then indicated what she wanted by draping cloth on and around dummies, as Poiret had done on living women.

She understood that cut was of first importance, it implied fit. She always contended that garments perfectly cut and perfectly fitted would remain smart long after the fashion which they followed was forgotten. She understood the modern craving for colour and a forceful, slenderizing line, and duly produced clothes of stylized simplicity. Indeed she always proclaimed that simplicity of line was the key to the distinctive, elegant silhouette, and symmetry its stamp.

She delighted in contradictions to shock, tease and amuse. She used traditional fabrics for the wrong garments; wool instead of silk, crepe instead of wool, crepe de chine for coats, felt for day suits and evening jackets, crinkled taffeta for top coats, jersey for gloves, calfskin for a three quarter evening coat, meshy gold fabric for lumber jackets.

In prints, Elsa let her imagination run riot. Poiret had been the first to introduce an artist, Raoul Dufy, to design prints for fabrics in 1911. Elsa persuaded Salvador Dali, Christian Bérard, Cocteau, Vertes and other artists to provide her with ideas. A series of “lucky dresses “in 1935 had the Great Bear or Big Dipper image of Elsa’s childhood. The Telegram Print was a joke in itself for the message: All is well, mother in law in terrible shape.

As far as colours are concerned, the first true colour chock she introduced was ice blue in 1932. Startling colours became a hallmark of the House of Schiaparelli. By adding magenta to pink an iridescent cyclamen coulour, the shocking pink became the colour whole dominating the whole collection of 1936 and her hallmark.

Trimming and Trappings:

Whereas Vionnet used embroidery to enhance a dress, Schiaparelli designed a dress to enhance embroidery. This was typically true of her boleros and black suits. Ordinary buttons symbolized utter boredom for Elsa and she persecuted them with the zeal of a reformer. She never bought a single one. Most were fashioned by Jean Clément, who baked them in a tiny electric oven. None looked the way a button was supposed to look. Many were found where never a button should be: on a hat for instance. And each one took on the importance of a carefully selected ornament. Lacquered button substitutes became one of the most striking features of her house. They were made of everything under sun: hand carved wood, aluminium, china, celluloid, metal, amber, coloured crystal, white jade and sealing wax. She initiated the use of ceramics as fastenings for suits and coats. She had terracotta objects dyed to represent lemons, grapefruits, egg plants and oranges.

Schiaparelli rendered the mundane delightful : buttons in the form of shoelaces, flower filled crystal paperweights , spinning tops, spoons, padlocks, lollipops, Christmas tree bells, coffee beans, fish hooks, safety pins, paper clips . She launched the dollar sign button in 1933, only to see the dollar collapse.

For belts, she was the first to use a wide curved belt which was relaunched with the new look afterwards. She adapted polo player and peasant waistbands and pioneered the importation of Australian kangaroo leather. She exaggerated stitching as a feature of design. Clement had him stitch by hand, using two needles instead of one, which gave an irregular and individual effect.

Bags were shaped like an old fashioned portemanteau, a suitcase, a flat bottomed satchel, a flower pot or a lifebuoy. Elsa has introduced beach bags with cord straps just long enough to be slipped up the arm to the shoulder. She developed the “bandolière”, the shoulder strap bag inspired by the the French railway guard’s bag.

Her innovative use of dyes was perhaps most apparent in her furs: red, green and bright blue fox, burgundy red sheepskin, pastel ermine, marten bewilderingly dyed to resemble mink.

She claimed justifiably that it was more of an art to create what she did not hesitate to call “junk jewellery” than the real thing, since the latter has intrinsic beauty of substance and did not require skill in combination. She always took care to moderate the effect of her more outrageous jewellery by placing it on severe clothes. She understood that being daring with allowed women to assert their individuality. One of her most charming ideas was to pin a little diamond brooch to the centre of a fresh rose, a habit adopted by chic women the world over. Cecil Beaton designed the Heart Clip, pierced by a rose and dripping iridescent rubies. Giacometti designed two bronze clips, but too heavy to commercialize but also phosphorescent flowers, to guide women in the darkened streets of Paris at the beginning of the war. Louis Aragon, the surrealist poet and his wife Elsa Triolet once designed necklaces that looked as if they were made of aspirins.

She has developed a long-lasting partnership with Jean Schlumberger, artisan of prosperous background, so far designing for a tiny set of stylish and artistic society leaders from her home atelier in Rue de la Boetie , taken over from Picasso. For Schiaparelli he designed some jewelled buttons in form of the Chinese pink starfish, a d’Artagnan plumed hat, speckled pebbles as well as ostriches. They sold like hot cakes. Both Schlumberger and Schiaparelli agreed that modern jewellery had gone flat and could only be given new dimensions by combining semi precious stones with precious ones. Soon Schlumberger for Schiaparelli became the rage and was copied at all prices.

Of all the daring and innovative accessories dreamed up by Schiaparelli, it is perhaps her hats that made the biggest impact. A particularly flattering hat she reasoned set beautiful women apart from others, while crazy hat acted as a defense against the insecurity of not having too pretty a face. In the history of costume, hats had not generated such fun and games since the times of Marie Antoinette. Her creativity had no limits; she developed hats like chimney pots, three bladed aeroplane propellors, ventilators, igloos, windmills or a bird cage containing a singing canary.

Approach:

Her courage was without limit, her approach fearless even daredevil. When she began “devising” she had, by her own confession, no idea what she was doing, she relied on her instinct, and never knew what would result. She used color with an artlessness that was the other side of genius. She was imbued by Paul Poiret with admiration, for the technical skill of Jeanne Lanvin and the artistry of Madeleine Vionnet, but she never acquired any greater learning than that. So she was hampered by none of the dressmaking traditions.

She held that twenty percent of women have inferiority complexes and seventy have illusions and on that basis she worked out her sales policy. She also trumpeted far and wide a new precept for buying clothes “Accepting cheap substitutes for real values will not bring about a return to prosperity. Everything that is cheap and quickly perishable is an extravagance no women can afford. One well cut beautiful dress is the luxury allowed to a shaky budget.”

She opened in 1933 a branch in London, at 36 upper Grosvenor Street, where she also lived in the 2 top rooms of this building when she was in town. In 1935 she took haute couture to the Soviet Union. Stalin deciding to open Russian frontiers to the western world, announced that the first soviet trade fair would be held in December 1935 and that it signified a new plan to raise the soviet standard of living. He invited the French government to send displays from its light industries from spinning mills textile manufacturers, perfumers, champagne producers and department stores. To show the Russian working girl what she should wear the French sent Elsa, accompanied by Cecil Beaton.

In 1947 strikes stopped work before she finished preparing her collection. Instead of canceling her show, se turned the showing into a sensational publicity stunt by displaying items with one sleeve, bringing to life half finished evening dresses, and pinning to them explanations about cut written in her bold handwriting with swatches of fabric and sketches to show where buttonholes would be. This was the cheapest collection she ever designed, and it sold very well. In 1952 she was too late with her official request to the Chambre Syndicale to obtain a suitable date for the presentation of her coming collection. So she scheduled it at midnight at her home asking a film company to transform her courtyard into a showroom out of a fairy tale.

At her height Elsa had 600 employees making, promoting and selling 10 000 items a year, some of these costing as much as 5000 $ each. In two major and two minor collections she presented 600 models annually.

The current of the opening of the twentieth century demanded a Poiret, but the war had forced him to quit the Parisian scene, the twenties had turned him down. In an exact parallel, the currents of the twenties and thirties had demanded a Schiaparelli but she had been forced to leave Paris by the Second World War and had likewise lost her sense of touch, now the late forties and fifties turned her down. Modern as represented in fashion by Schiaparelli in the thirties, was now passé. Contemporary was in. While continuing to answer the need for new forms for the burgeoning technologies, the contemporary concept aimed to increase efficiency, comfort and visual enjoyment by outlawing whatever had been strange in the preceding decades. Schiaparelli never lacked inspiration, her designs remained beautiful and she never betrayed women, but she was not in tune with the prevailing mood and even felt uneasy. Her approach of calculated shock and frivolity no longer corresponded to the spirit of the day. A new look – younger, more romantic, softer- was in the air before the New Look. Balenciaga had announced it as early as 1937 when inaugurating his Paris house.

The fledging post war couturiers Fath, Balmain, Piguet, Desses, all reflected the need to restore unforced femininity to women after the dreary years of utility. The New Look was the ultimate commercialization of the rounded lines that had been seen since the first post liberation collection: no revolution and rather a new use of themes which had been crystallizing for seasons past but now seemed fresh and inviting.

In 1954 Schiaparelli showed her farewell collection, featuring the free and elegant Fluid Line. She continued to receive celebrities at her home in Paris, also in Hamamet, Tunisia. «Young designers can no longer do what they like because of the pressures on them to produce lines that sell for a certainty. The daring is gone. No one can dream anymore. Consequently she bought almost exclusively from her friend Balenciaga, the only designer besides Saint Laurent, who could still afford to follow his dream and dare to do what he liked. The young newcomer YSL, determined to uphold the grand tradition of Parisian beauty and elegance that Schiaparelli appreciated and supported from his first collection, and she bought at least one model from him each year.

The fashion world did indeed revive her style at the end of the seventies, but how forced it all was. Her avant garde had become the norm, her modernism was now conventional. However the philosophy of Elsa Schiaparelli was to urge women to dare to appear publicly in theatrical clothes, not only to assert their independence but also to provide glamour, fun and romance in their daily lives. Along with her masculine styles, she drew the fancy dress and masquerade balls out of private mansions and on to the streets. Wear the smartest of what is conventionally permitted; yes, but also be the most exciting of your own unique self while remaining fashionable

She was the undisputed queen of Paris fashion from 1935 to 1939 but her influence in the fashion history is huge.